This huge andesite lava boulder is located in the Borrowdale valley in Cumbria, England. It was formed from lava that was ejected out of an ancient volcano. Approximately 13,000 years ago this rock was about 200 metres above where I stand and formed part of King"s How, a mountain that rises steeply on my left in the photo. The movement of a glacier shaped and fragmented the sides of the valley and possibly dislodged the Bowder Stone, which eventually fell down the mountainside at an unknown date and landed in its current position here, balanced on one edge.

Now that summer is over, don’t you just hate it when someone gets out their ‘holiday snaps’ and regales you with stories of their last trip? Unfortunately, that is exactly what I am about to do! However, as you might have guessed, my photos are not of me lounging on a Mediterranean beach. My photo is of me sitting by an ‘old stone’ in a wooded valley in the Lake District.

The stone in question, the Bowder Stone, is said to be one of the largest natural freestanding boulders in Britain. I did not purposefully set off to Cumbria to visit the stone; even I’m not that boring. Whenever I visit a part of the country that is new to me, early in the holiday, I always try to pick up books on local folklore, ghost stories, history and the like. The first such book I acquired on my trip to the Lakes was a little booklet by a retired Geologist, Alan Smith, entitled ‘The Story of The Bowder Stone’, published in 2003. I had never heard of the Bowder Stone before and the booklet looked interesting. Imagine my surprise then, to find that the Stone has a strong Nottingham connection

.

The Stone and its Geology: The name Bowder Stone appears in many different variants throughout its recorded history including; ‘Boother-stone’, (William Gilpin, ‘Observations relating to Picturesque Beauty’, 1772), ‘The Bowdar Stone’, (Hutchinson, ‘History of the County of Cumberland’ 1792), and ‘Powder or Bounder Stone’, (James Clarke, ‘Survey of the Lakes of Westmorland, Cumberland and Lancashire’ 1792+). There have been suggestions that the name may be derived from ‘Balder’, the son of the Norse god Odin, however, it is more likely that it is a variant on the local dialect of the word ‘boulder’.

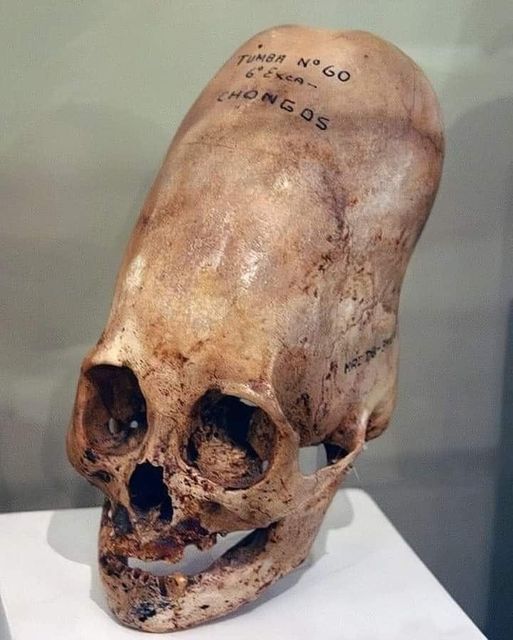

The Bowder Stone is situated in Burrowdale deep in the heart of the Lake District, at the southern end of Derwentwater, around 41/2 miles south of Keswick. It lies just under half a mile east of the B5289 in the narrowest point of the valley, known as ‘The Jaws of Burrowdale’. It is an extremely large, rectangular, box shaped boulder of ‘fine grained, dark greenish grey, andesite lava’. This lava spewed from a volcano sometime during the Ordovician period of the Palaeozoic Age, 485 – 443 million years ago, (far older than any of Nottinghamshire’s ‘old stones’). At around 59’ high and 26’ along its broad side, with an estimated weight of 1253 tons (Smith), its amazingly regular shape is entirely the product of nature.

Smith states that the Stone does not appear to feature in Cumbrian folklore, however this is not true. There is a tale of how the Bowder Stone came to be where it is. All over Britain there is a legend which states that when the first humans settled in these isles, they found the land inhabited by a race of giants. A war for the control of the land broke-out between the human settlers and the giants, – the giants were defeated. The Stone is said to be a missile thrown by one of the hapless giants at his human adversaries. The truth of the matter is somewhat more mundane but never the less amazing.

Sometime around the end of the last Ice Age, around 10,000 years ago, the action of centuries of severe cold fractured the exposed strata of andesite lava on what is now Bowder Crag on Kings How over 850’ above the site of the Bowder Stone. The result was a massive ‘rock-fall’, with the Bowder Stone as the largest surviving chunk of debris. Smith says that evidence of this cataclysmic event can be found all over the slope above and around the Stone.

The Bowder and its ‘tourist steps’ from the west.

The Bowder Stone from the north. “….perched on one corner like a performing elephant on one leg.” (Norman Nicholson, Great Lakeland 1969)

On the very first page of his book Alan Smith states that; “The Bowder Stone is one of the most popular visitor attractions of the Lake District.” How the Stone achieved this remarkable status is due entirely to the efforts of a Newark man with a Yorkshire name, Joseph Pocklington.

Joseph Pocklington, 1736 – 1817: Joseph Pocklington was described by one of his contemporaries as; “A man of no taste whatsoever.” For the modern historian, he is somewhat a difficult character to put a label on. One thing is certain by the standards of any age he can be counted as an eccentric. His eccentricities left their mark on the landscapes of at least two counties and famously upset Wordsworth and Coleridge, the Lakeland Poets.

Pocklington was an extremely wealthy man who acquired a number of country houses and estates in both Nottinghamshire and Cumbria. A common myth surrounding the source of his wealth suggests that he was a banker. However, this is not confirmed in any of the records of the time and is largely due to confusion with a family member of the same name. The Pocklington family had its origin in Yorkshire taking their identity from the village of that name. By the late 17th early 18th century this large and prosperous family had established numerous branches in and around Newark and parts of Lincolnshire. Much confusion occurs due to the common usage of the given names William, Roger and Joseph for male members of the family. Pocklington was himself aware of this confusion and wherever he recorded his name he added his current residence, i.e. ‘Joseph Pocklington of Newark’.

Joseph Pocklington was born in Newark, the second son of William and Elizabeth Pocklington (Rastall). He was educated at Wakefield Grammar School and went on to Jesus College Cambridge but did not finish his degree, leaving at the same time as his brother Roger. He then seems to have embarked on a tour of the British Isle, producing a sketchbook of his travels the ponderous title of which sums up his early life and later fetish for buildings and architecture:

‘The following are the rough plans and elevations of Castles, Houses, Druid Temples, (pre-historic monuments), Ruins, Bridges, Islands, Cascades, Landskips, Inscription etc. etc. which I took upon the spot when I rode into different parts of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland on journeys of pleasure and most faithfully drawn by me Joseph Pocklington of Carlton-on- Trent Nottingham. Never yet published or intended to be.’

In 1751 Josephs grandfather, another Roger and the source of much of his inherited wealth, died in rather strange circumstances: ‘….his death was occasioned by the wall of his apartment blown down by a violent storm about a week before, which fell on the bed where he lay and broke his thigh’ (Gentleman Magazine 1751). With the death of his grandfather Joseph inherited one of the first of his many Nottinghamshire estates, the manor of North Muskham and Batheley and immediately set-about building a new manor-house, Muskham Hall, to his own design.

The year 1778 saw Joseph become one of the first new ‘pioneers’ to settle in the Lake District admiring the region entirely for the beauty of its landscape. His first acquisition in the Lakes was Vicar’s Island in Derwentwater. He immediately changed the name to Pocklington Island, – offending the locals, – and set about building a large mansion, again to his own designs. Not content with the house he went on to re-landscape the entire island building boathouse, fort and battery, and a druid temple.

Pocklington passion for building now became an obsession and he acquired further land around Portinscale near Keswick where yet again he built a large house. Pocklington constructed the third and most lavish of his Lake District properties in 1787 when he purchased land at Barrow near Ashness on the eastern shore of Derwentwater. Not one of Pocklington’s properties were appreciated by any of his contemporise, (except perhaps his family) and he now became known for his crass lack of taste.

‘Barrow House’, the most lavish of Joseph Pocklington’s Lake District properties.

Joseph Pocklington’s building and landscape work in Cumbria brought him nothing but criticism from the ‘great and the good’ of the county. The poets Wordsworth and Coleridge openly mocked his work whilst the common man referred to him as ‘King Pocky’. Undeterred by this criticism, Pocklington continued to impose his idea of the ideals of landscape upon the many acres he owned.

In 1798 Pocklington applied his attentions to ‘improving’ the land he had acquired in Borrowdale. This land, along the side of the main road through the valley, – now a footpath/track, – contained the site of a popular local treasure, The Bowder Stone. Pocklington was fully aware of the sites potential as a tourist attraction, but it did not match his view of a ‘romantic landscape’. The first job he undertook was to clear all of the loose material around the base of the Stone. For the first time, this revealed the Stone in all its curious glory. True to his nature, Pocklington meticulous recorded the Stone’s dimensions to the extent of mathematically estimating it weight.

Next he built a fence around the Stone and the first permanent ladder to admit the public to its summit. A short distance from the Stone, Pocklington erected what he termed a ‘Druid Stone’ – a pre-historic monolith. Befitting an ancient magical place, Pocklington designed and built a mock hermitage or chapel and to control access to his ‘visitors attraction,’ a single story dwelling, – ‘Bowderstone Cottage’, – for the site’s caretaker and guide. Perhaps to conform to Georgian sensibilities, Pocklington installed a female guide in the cottage.

Pocklington’s idealized landscape around the Stone gave it the perfect false history mimicking that of other natural features like sacred springs; a natural feature which became a Druidic monument and was Christianised by the presence of a hermit’s chapel. This would have been something that the educated tourist and visitor of the day would have instantly recognised without being told. To make things more interesting, by pure chance Pocklington was able to create a new legend or tradition associated with the Stone. On clearing the Stone’s base, a natural hollow running under its north south axis was discovered. Pocklington had a small hole drilled through the base of the south-eastern side of the Stone, thus connecting the hollow with the outside world. It then became possible for those able to crawl into the hollow to ‘shake-hands for luck’, with a fellow visitor lying down on the outside of the Stone.

The stage was now set for the opening of Pocklington’s tourist attraction. To begin with Pocklington personally took his friends and guests by carriage down the rough road through Borrowdale to the Stone. Here they were greeted at the rustic cottage by his lady guide who, suitably scripted by Pocklington, would conduct her tours. From this humble beginning tours of the Bowder Stone soon became the highlight of the tourist round.

King Pocky’s reign in the Lake District came to an end when he died at one of his Nottinghmashire properties, Muskham Hall, in 1817, just 7 years after his brother Roger. Muskham hall was demolished in 1830. However, the Bowder Stone passed into new hands and continued as a popular tourist venue throughout the Victorian era and well into the early 20th century. Broken only by the presence of John Raven, the role of guide continued in the tradition of being female. Mary Caradus the guide in the 1830’s, was succeeded in the 1850’s by Mary Thompson who was in residence at Borrowdale Cottage for over 25 year.

The Bowder Stone is now in the care of the National Trust. The hollow beneath the Stone is no longer accessible; Pocklington’s chapel has been demolished, Borrowdale Cottage is now a ‘climber’s hut’, the ladder and Druid Stone remain.

In writing this article I am left wondering what would have happened if Joseph Pocklington had acquired one of Nottinghamshire’s ‘Old Stones’, – the Hemlock Stone or perhaps Blidworth Rock (the Druid Stone)?

A Victorian photo of the Bowder Stone showing tourist on its summit